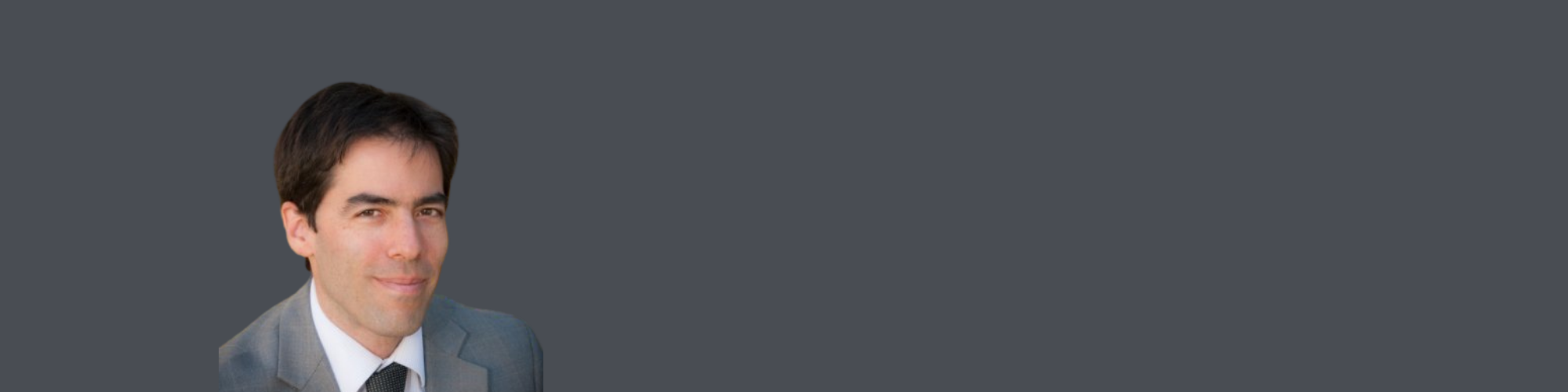

For David Shprecher, DO, caring for the movement disorders community is personal. Dr. Shprecher has been open about his journey with Tourette’s syndrome, a neurological disorder characterized by sudden, repetitive, rapid, and unwanted movements or vocal sounds called tics. With natural curiosity, imagination, and compassion born from his own journey, Dr. Shprecher has found a sense of home in his work: this is where he belongs.

In the interview below, he takes us back to the beginning, to his life as a kid and the moments he first noticed his Tourette’s symptoms. He draws us into stories about his challenges and the stigmas he faced, his desire to study neurology, and his work today.

Dr. Shprecher’s commitment to the movement disorders community is palpable; he has joined us on several Neuro Life Online® programs, as well as in-person workshops, and he’ll be speaking at our Advanced Therapeutics in Movement & Related Disorders (ATMRD) Congress in Washington, DC, in June, a first-of-its-kind congress that will engage residents, movement disorder fellows, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, neurologists, geriatricians, family practice providers, and more, in robust discussions on the latest clinical science. He knows that when healthcare providers are empowered with the most innovative research and access to hands-on trainings for therapeutics like DBS and botulinum injections, it’s the people living with movement disorders and their care partners who benefit the most.

Here’s our interview with Dr. Shprecher:

David Shprecher, in the blue glasses, at his 10th birthday party.

Paint a picture of who you were as a child and what you loved to do.

My friends and I had wild imaginations, inspired by Lord of the Rings type fantasy stories. We used to wander the forests of our neighborhood pretending we were knights and wizards, and later discovered Dungeons and Dragons. (I liked to be the Dungeon Master.)

When did you or your parents start noticing your Tourette’s symptoms?

I remember probably in the first grade one of the girls in my class asked me to stop making funny noises during quiet time (I didn’t think much of it). Then, maybe in 4th or 5th grade, another boy making fun of the way I used to scrunch my nose all the time. In my early teens, I got a bit obsessed with working out and used to have this urge to hit myself in the stomach to make sure my abs were solid. My best friend joked once that I was not allowed to hit myself when I was at his house.

David at age 16 in red shirt & blue shorts.

As a kid, what did you understand about having Tourette’s?

My parents took me as a teen to see a neurologist when I was struggling with the other issues common in kids with Tourette’s. The neurologist explained about obsessive compulsive disorder (at that point I was setting too many diet and exercise rules for myself and it wasn’t healthy) but, as far as I recall, he didn’t really talk about tics or Tourette’s.

Did you ever experience a sense of stigma? How did that make you feel?

Early on there were some misunderstandings. For example, I had a tic where I felt like I had to press my stomach and make my tongue stick out. This happened right when my friend’s mom came in to ask if we wanted snacks. (He kicked me out of his Dungeons and Dragons group after that, but I just started my own.) Once a neighbor saw me shaking my head vigorously while I was out for a run and asked if I was OK.

Did your experience with Tourette’s influence your desire to become a doctor and, eventually, work with people with movement disorders?

As a young adult I had read about chronic tic disorders in Oliver Sacks’s books and had a sense that these could explain the movements and sounds that I made. It wasn’t until I went into neurology residency that I had an opportunity to study about Tourette’s and confirm that’s what I had.

David, age 19, in college.

How has having Tourette’s syndrome impacted your professional life?

I chose to pursue movement disorders training in part to better understand the condition that I have. It has been rewarding to help people get earlier, more useful advice about their own conditions.

Do you find it has given you an added sense of understanding and compassion for your patients?

Yes. For example, in my early 20s (before I went to medical school) I remember telling myself that if I just tried harder, I could just stop my tics and they would go away. So I understand that pressure we can put on ourselves for something we cannot really control. It is sometimes helpful to be able to tell young people from experience that the tics may never completely go away, but they can learn to live with them and manage the other symptoms.

Tell me a little about the work you do today.

The movement disorder field is very diverse and includes a wide range of conditions and consultation questions. I need to take all my knowledge and experience, use a range of electronic tools (and occasionally textbooks), and come to a diagnosis and plan of treatment. In a sense it is like being a bookish detective.

David Shprecher, DO, Msci FAAN, is a Movement Disorders Director at Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Sun City, Arizona and a Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Arizona. Dr. Shprecher earned his medical degree from Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine. He went on the complete his neurology residency at the University of Utah School of Medicine and his movement disorders and experimental therapeutics fellowship at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. Prior to joining Banner Health in 2015, he started the movement disorder clinical trials, Tourette Association of America Center of Excellence and Huntington Disease Society of America Center of Excellence programs at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Inspired by personal experience as an individual with Tourette syndrome, he has dedicated his career as a movement disorders neurologist to improving treatment options and quality of life for movement disorder patients. In addition to a long history of site investigator activities in movement disorder clinical trials, his observational research with Banner’s Brain and Body Donation Program and the North American Prodromal Synucleinopathy Consortium is aimed at improving early diagnosis of, and biomarkers for, REM sleep behavior disorder.